Dear T,

Strangely enough this was exactly why he became popular. Eventually we like to be on the inside of a conspiracy, and a mirror look at mass delusion outs one of them. So he trashed us and we took it. We bought the sayings for centuries now, and chewed on them, and realized things about ourselves that we'd rather not say out loud, and spotted them (or thought we spotted them) in others, and felt the wiser for it. Like Diogenes the Cynic and H.L. Mencken, Rochefoucauld was a hero to many of us not for building anything beautiful, but for taking a wrecking ball to our pretensions -- a much needed job in any society, like plumbing. But not everyone can handle crawling in sewage. Most prefer to hide in a room and flush it away -- an aspect of us which is also admirable, in its own sense.

Rochefoucauld's collected sayings are fun to read -- and then to burn. They're too uncomfortable to think about too long, and Oxford World's Classics, in the introduction to his book, lists every excuse people use to pretend the sayings don't apply to us.

First is that we take a "broader" view of humanity, and thus a less cynical one. Or that the sayings are inconsistent and contradict themselves -- which can be said of many truths in general. Or that they're only true of Rochefoucauld. Or maybe that they're true of most people (but not us). Or that they're only true of us at our worst. And finally if they are true of us, we sweep them under the rug and forget we ever read them. The age of self-esteem for fatties and good-for-nothings has seen the absolute disappearance of Rochefoucauld. Did time sweep him out of our consciousness? Or did our participation-trophy parents get too soft to pass him on?

This book of short, brutal, and many times brilliant statements was so offensive to people's self-esteem that it was thought to be against their very religion -- a rejection Rochefoucauld saw coming, and for which he hired a lawyer to write the preface. He was worried that his attacks on our moral pretenses would be taken as an attack on morality itself; and so far from being an amoralist, he intended to show us who we really were -- not an attack on all goodness, but an attack on our fakeness. And if all of these aren't right about all of us all the time he was still right. We are rotten. And he's right that we're experts at hiding it.

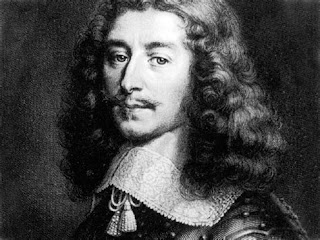

|

| Francois VI, Duc de la Rochefoucald |

A few gems:

The love of justice is simply in the majority of men the fear of suffering injustice.Old men delight in giving good advice as a consolation for the fact that they can no longer set bad examples.

A man is perhaps ungrateful, but often less chargeable with ingratitude than his benefactor is.

Men would not live long in society were they not the dupes of each other.Everyone blames his memory, no one blames his judgment.Nothing should so much diminish the satisfaction which we feel with ourselves as seeing that we disapprove at one time of that which we approve of at another.Sincerity is an openness of heart: we find it in very few people. What we usually see is only an artful dissimulation to win the confidence of others.The hate of favourites is only a love of favour.If we had no pride we should not complain of that of others.If we had no faults we should not take so much pleasure in noting those of others.The constancy of the wise is only the talent of concealing the agitation of their hearts.

Rochefoucauld was born in Paris in 1613, the son of a wealthy, famous aristocrat. He was married at 14, had most of his eight kids within twelve years, and got Louis XIV's cousin, the Duchesse de Longueville, pregnant out of wedlock. It was said by women close to him that he'd never been in love, and his maxims corroborate the theory. He writes in his own book, there are good marriages, but no rapturous ones, and the thing missing in love affairs is love -- two statements which cover all the bases*.

By 15 he was involved in politics and war. He fought the Spaniards in Italy and the Netherlands, and when he was done fighting them, he fought Louis XIV. He played both the patriot and the rebel, and was wounded a couple times, nearly to death. He spent stints in exile and the Bastille. And he tried to have Cardinal De Retz murdered -- cardinal as in, a cleric outranked only by the Pope. So you could say even as a young man he was pretty experienced in almost everything. Everything except literary things, anyhow.

Around 1657 he and a couple of aristocrats began writing epigrams for fun. But after a short while amusing each other it became clear he left them in the dust. Soon he had a collection people were sharing with their friends, with or without his permission, and he felt pressured to release an authorized version to the public.

This was when he hired the lawyer. Seeing things all too clearly, he knew that an attack on people's pride would be taken as an attack on their morality -- and, since Christianity is supposed to make men feel like saints, that in the end it would be taken as an attack on their religion. He maintained the opposite was true, and that in order to really appreciate and lean on Christ you'd have to have your pride broken. People swallowed this answer alongside many of the maxims, and the lawyer's preface was dropped from the second edition.

The question is, how true are his sayings? I would say many of them are, but to each of us the degree is different. And while we could take pride in pretending all of them are, because it takes a lot of honesty to admit so many terrible things about yourself, some of us have actually been in love, and some of us more than once -- and if we differ this much from Rochefoucauld in one way, and especially such a drastic way, we can differ from him in others too.

Yours,

-J

*I have no idea how a teenager could not fall in love, but I guess there are other reasons to romance than romance -- pride being one of them, and sport, and jockeying for a position in life. It may be that faking romance was what kicked off his whole schtick. If your love isn't real, then what is? You have to start looking for ulterior motives in everything else.

Thus Rochefoucauld writes about virtue,

What we term virtue is often but a mass of various actions and divers interests, which fortune, or our own industry, manage to arrange; and it is not always from valour or from chastity that men are brave, and women chaste.

And about love,

Love lends its name to an infinite number of acts which are attributed to it, but with which it has no more concern than the Doge has with all that is done in Venice.

One thing that "wise" people and "saints" have been conning us with for centuries is that all our good works are selfish. But the truth is that they're only complex. They pretend that if you earn money saving your country you're a mercenary, and if you save a beautiful woman you did it only for sex. But why not both? Why not be a patriot and get paid for it? Why only save a woman if you wouldn't have sex with her? Is it not love if you marry for personality and sex -- and prestige alongside them, or for money?

The "saint" believes two goods cancel each other out, or make for a sin. But the truth is that we can get ten goods out of a thing and none of them cancel out the others. If anything they add to them. The saints say your morals are a scam, and maybe the way we market them is. But what about the man who glorifies himself -- by mislabeling everyone's virtues? I remind you that in the Bible, the Devil's original name is The Accuser.

**Not all of his maxims were caustic. Many of them are just plain wise, or interesting, and I've included some here for fun.

Neither love nor fire can subsist without perpetual motion. Both cease to live so soon as they cease to hope, or to fear.There is no disguise which can long hide love where it exists, nor feign it where it doesn't.There are no accidents so unfortunate from which skilful men will not draw some advantage, nor so fortunate that foolish men will not turn them to their hurt.

We promise according to our hopes; we fulfill according to our fears.

We have more strength than will; and it is often merely for an excuse we say things are impossible.People are often vain of their passions, even of the worst, but envy is a passion so timid and shame-faced that no one ever dare avow her.

Philosophy triumphs easily over past evils and future evils; but present evils triumph over it.

We all have sufficient strength to support the misfortunes of others.Our self love endures more impatiently the condemnation of our tastes than of our opinions.

The whole collection can be had for free on Amazon.

Start your subscription today. Get my free ebook essay collection by emailing me at letterssubscription@gmail.com!

Comments

Post a Comment